|

|

BLOG

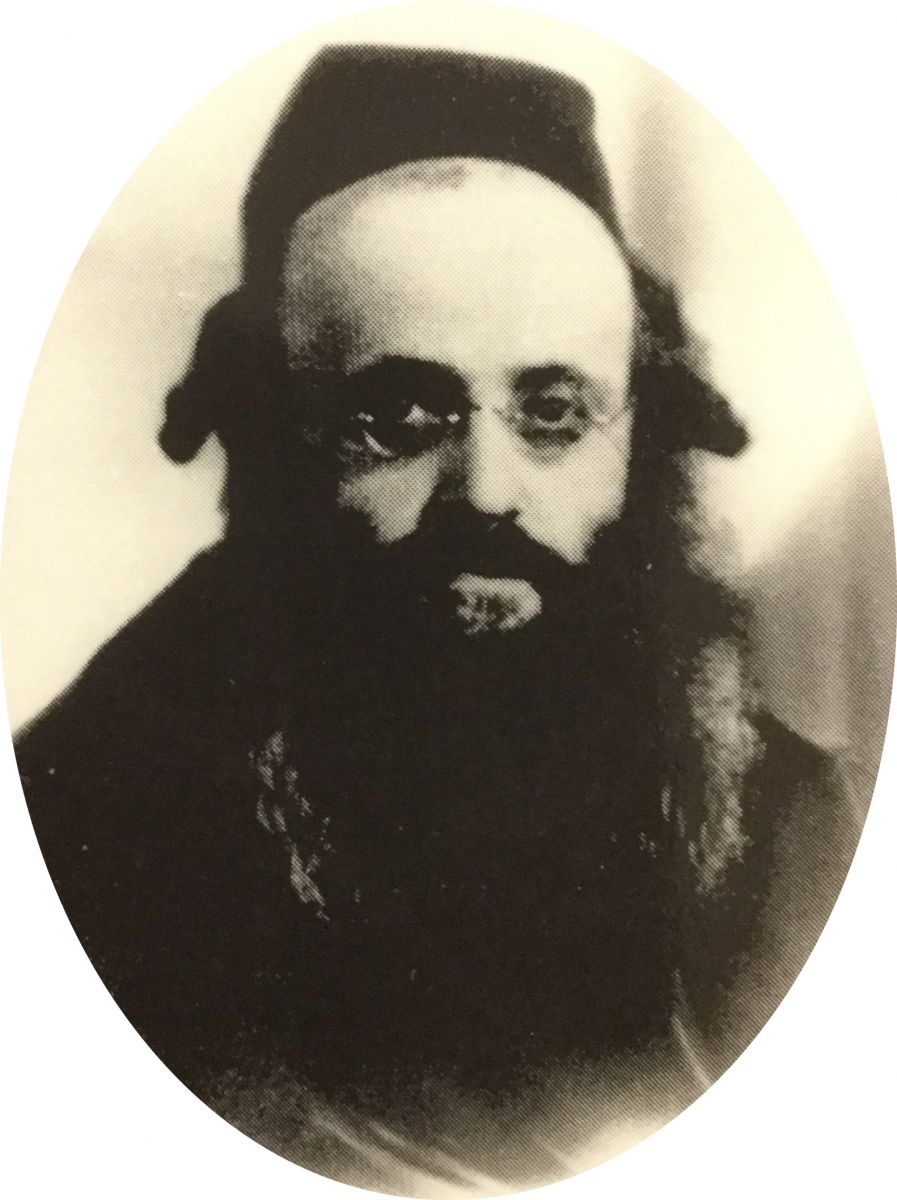

What We Can Learn From How a Hasidic Rabbi Comforted the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto

When Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira penned his last will and testament, he did not know if it would ever be read by his relatives in Israel—or anyone, for that matter. In January 1943 the Ghetto was deserted, bereft of the hundreds of thousands of Jews that once crowded inside its walls.

When Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira penned his last will and testament, he did not know if it would ever be read by his relatives in Israel—or anyone, for that matter. In January 1943 the Ghetto was deserted, bereft of the hundreds of thousands of Jews that once crowded inside its walls.After three years of starvation, disease, and senseless random violence, the Nazis had engineered the near-total destruction of the Jewish population by deporting them to the death camps, 6,000 per day, until only a few thousand were left to toil as slave laborers in a number of urban industries. The hundreds that once congregated to hear Rabbi Shapira’s Sabbath sermons were long gone, their holy spirits disgorged from Treblinka’s crematoria as smoke and ashes.

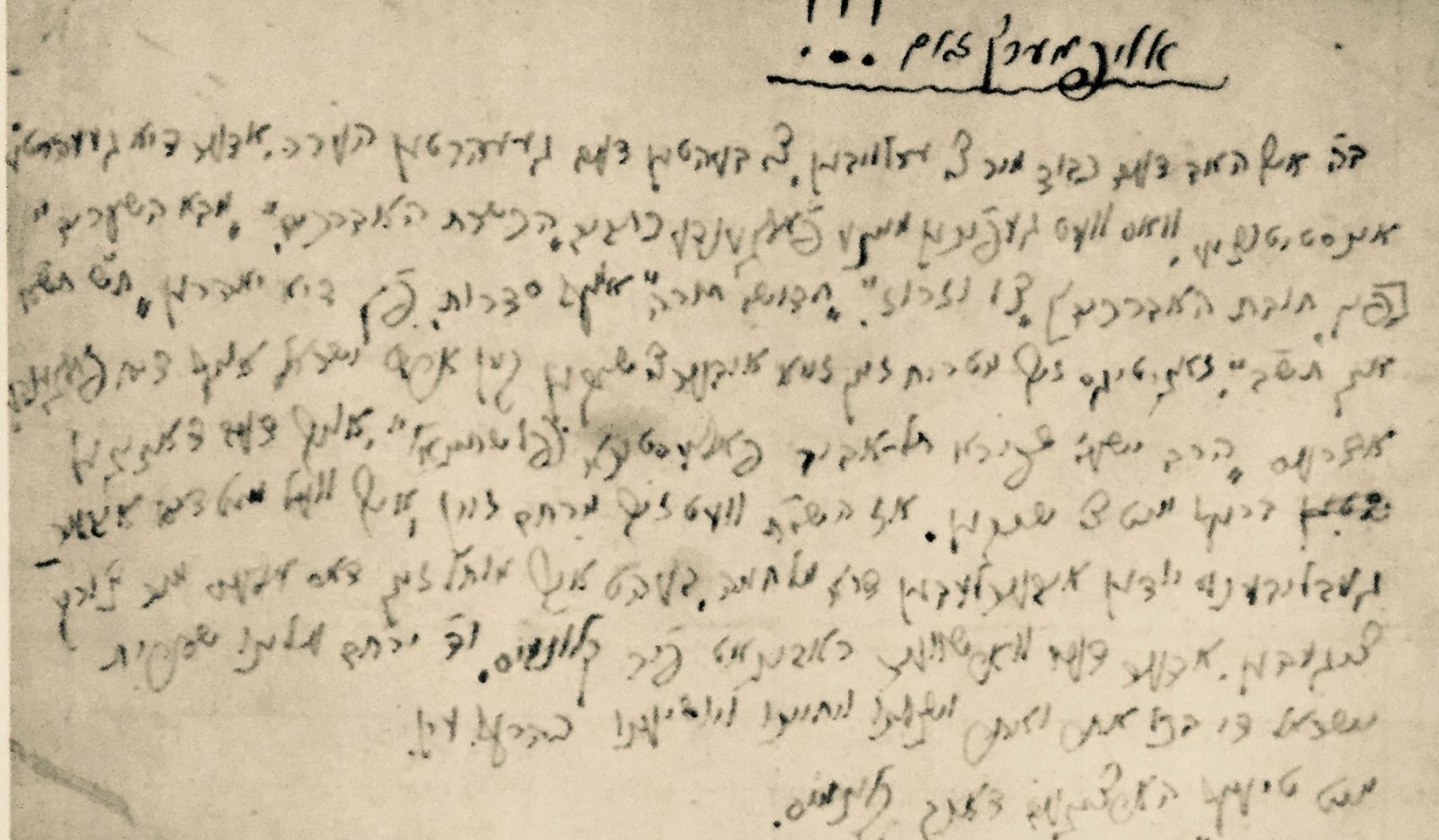

With his Hasidim gone, the Rebbe gathered up his tear-stained manuscripts and handed them over to the Jewish underground historical society, code-named Oneg Shabbat, for burial. For seven years the Rebbe’s weekly sermons remained entombed in a tin milk container under 68 Nowolipke Street, until a Polish construction worker discovered them while clearing the rubble of the ruined Jewish quarter. Published in 1960 under the title Aish Kodesh (Holy Fire), the Rebbe’s Holocaust writings constitute an incomparable testament to the power of emunah—faith—despite unimaginable suffering.

The Rebbe’s prominent position as the head of a major Rabbinical Seminary and the author of a massively popular book on Jewish education (The Obligation of Students, 1932) did not afford him any protection from the Nazi horrors. Early on in the war the Rebbe experienced personal tragedy.

The Nazis bombed the city mercilessly in preparation for their invasion, and shortly after Yom Kippur 1939 the Rebbe’s only son was grievously wounded by shrapnel. The Rebbe, together with his daughter-in-law and the Rebbe’s sister-in-law, rushed the young man to a local hospital, teeming with the wounded. Conditions were dire in the overcrowded facility, so the Rebbe left to search out a local doctor, with the two women standing outside the hospital entrance reciting Psalms and praying for Rabbi Shapira’s survival.

While the Rebbe was away, the Luftwaffe dropped another deadly load directly over the hospital, killing the two women. The Rebbe’s son succumbed to his wounds a few days later, on the second day of Sukkot; shortly thereafter, the Rebbe’s grief-stricken elderly mother also passed away. The Rebbe did not disturb the holiday with outward sign of distress, as Jewish law required, collapsing into grief only at the conclusion of Simhat Torah. He delivered no sermons during the thirty-day mourning period.

When he regained his public voice—on the week when Jews worldwide read of the Abraham’s mourning for the death of his wife Sarah—he delivered one of the most powerful and poignant meditations on emunah amidst tragedy in the entire corpus of Jewish literature. Somehow, the Rebbe managed to express his personal anguish and his inability to understand the justification for their deaths without impugning his elemental, fundamental faith in G-d.

As the war dragged on, the Rebbe would call upon his deep reservoir of faith again and again on behalf of his beleaguered Hasidim, reeling from their own personal and communal tragedies. A close comparison of the Rebbe’s sermons with the specific events that occurred in the Ghetto—a new decree to construct the walls, a typhus outbreak, a massacre of innocent Jews as a token collective punishment for an isolated act of disobedience—demonstrates that the Rebbe unerringly looked to the Torah for messages to reinforce emunah among his Hasidim.

For example, in the spring and summer of 1940, the Jews in Warsaw placed much of their hopes in the ability of the French to throw back the German invader, much as they had emerged victorious from the First World War. Rumors flew along the streets like starlings, some insisting that the war would end in months, while others said it was a matter of days. The fall of Paris in June came as a crushing disappointment: the Nazi victory meant that Hitler now dominated all of Europe, from the Soviet border to the English Channel. The Thousand-Year Reich looked like it would become a reality, with horrific consequences for the Jewish people.

The Rebbe, however, would not succumb to despair, and he refused to allow his Hasidim to abandon their faith in G-d. The Torah portion of that week dealt with the report of the spies: ten of them were ready to give up hope in the Promised Land, complaining that the inhabitants were giants, the cities were impossible to conquer, and so on. The Rebbe, on the other hand, focused on the message of Caleb, whose trust in G-d represented a dissenting message.

Such must be the faith of the Jew. Not only when he sees an opening and path to his salvation, that is that he reasonably believes, according to the course of natural events, that G-d will save him, and thereby he is strengthened; but also at the time when he does not see, Heaven forbod, and reasonable opening through the course of natural events for his salvation, he must still believe that G-d will save him and is thereby strengthened in his faith and trust... He must declare that it is all true, that the nation that lives there is in fact powerful, it is true that the cities are fortified. Nonetheless, I proclaim my faith in G-d, that God is beyond limitation and nature that G-d will save us... Such faith and trust in G-d draws our salvation closer.

Ultimately, the Rebbe was deported to the labor camp Trawniki and martyred there. His luminous message of emunah amidst tragedy lives on as an example of boundless spiritual heroism.

Henry Abramson’s most recent book is Torah from the Years of Wrath 1939-1943: The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh.

---

Have something to add? We'd love to hear from you. Please comment below to share.

Can one be Jewish and not believe in God? See answers from Orthodox, Conservative and Reform rabbis here.

Can one be Jewish and not believe in God? See answers from Orthodox, Conservative and Reform rabbis here.If you have a question about Jewish values that you would like to ask rabbis from multiple denominations, click here to enter your question. We will ask rabbis on our panel for answers and post them. You can also search our repository of over 700 questions and answers about Jewish values.

For more great Jewish content, please subscribe in the right hand column. Once you confirm your subscription, you'll get an email whenever new content is published to the Jewish Values Online blog.

For more great Jewish content, please subscribe in the right hand column. Once you confirm your subscription, you'll get an email whenever new content is published to the Jewish Values Online blog.

|

|

|

Jewish Values Online

Home | Search For Answers | About | Origins | Blog Archive Copyright 2020 all rights reserved. Jewish Values Online N O T I C E

THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN ANSWERS PROVIDED HEREIN ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL JVO PANEL MEMBERS, AND DO NOT

NECESSARILY REFLECT OR REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE ORTHODOX, CONSERVATIVE OR REFORM MOVEMENTS, RESPECTIVELY. |