|

|

BLOG

The First and Only Hasidic Female Rabbi

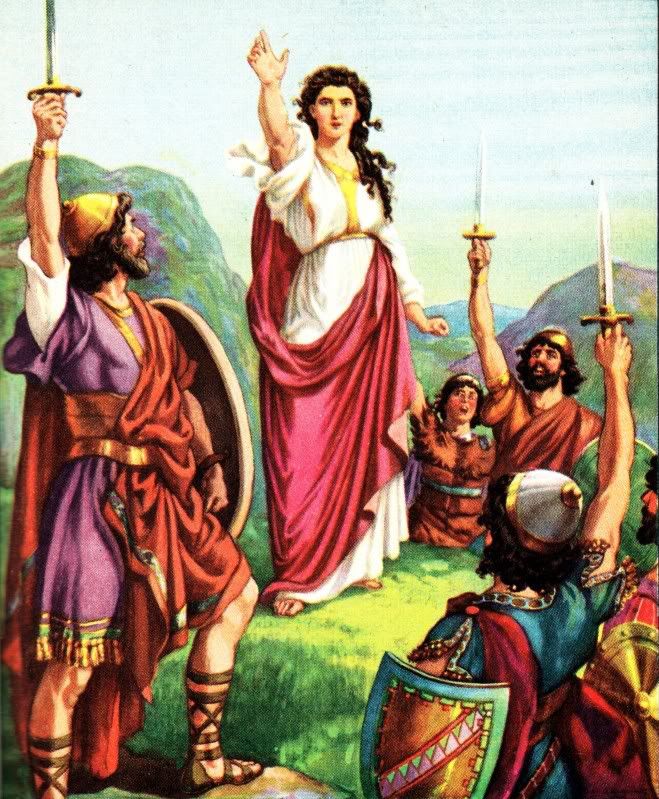

Imagine a woman standing in front of a congregation, tefillin and tallit adorn, expounding on the weekly Torah portion.

Now this is nothing new, you may be thinking. Within the non-Orthodox Jewish sphere scenes like this occur weekly and hardly merit any special attention. While the battle of female equality in the context of Jewish practice and rabbinic leadership is still being waged in Orthodox quarters - within its Reform and Conservative counterparts this is a long outdated conversation.

But what if I told you that this woman, Hannah Rachel Verbermacher, was a Hasidic rebbe who frequently delivered sermons to hundreds of followers from behind a fixed bed sheet that acted as a mechitza in her study hall.

And Verbermacher wasn’t just the first female Hasidic rebbe ever. She was, in all probability, the earliest woman rabbi in history (in any denomination) living over 100 years before the “first” female rabbi, Regina Jonas. This enigmatic figure, the history of whom was long thought to have been lost to the realm of memory and myth, was finally resuscitated after years of archival research in the early 2000’s by the historian Nathaniel Deutsch in a book titled The Maiden of Ludmir: A Jewish Holy Woman and Her World.

Now learning about Verbermacher is not simply a fascinating story. Rather, Verbermacher was a deeply complex figure whose life story touches on issues of gender both in terms of her own individual identity and the general role of women within the deep seeded patricharcy of the Hasidic world.

Verbermacher was born in the year 1805 in Ludmir, a region of modern day Ukraine, to a pious and wealthy family. Her father, having no sons, wanted to ensure that Hannah had an extensive education - a rarity for females during that era. While not much is known about her youth there seemed to be nothing truly exceptional about the young Hannah. It was, rather, during her early teenage years that Verbermacher first began to stand out. When Verbermacher’s mother suddenly passed away, the fourteen year old seemed to have taken it particularly hard, frequently visiting the cemetery for hours at a time.

It was during one of these graveside visits that Verbermacher became extremely ill and was subsequently bedridden for days while she faded in and out of consciousness. It is here that Hannah Verbermacher would begin the path of becoming a Hasidic leader adored by many and hated by many more.

Some accounts tell us that when she fully recovered, Verbermacher suddenly knew as much Torah as the greatest rebbes of the time - including subjects in which she never had any formal teaching. More realistically, after this life changing moment, Verbermacher began to apply the knowledge of her youth, unashamed to reveal her inner genius. Regardless, however, of what exactly happened during her illness, the teenage Verbermacher began to take an increasingly “male” approach to Judaism.

Now it’s important to take a step back. I used the term “male” approach to Judaism not because I feel that this represents some greater truth or is even the best phrasing - rather it was exactly how many others have referred to Verbermacher over the years.

Early biographers began to refer to Verbermacher as a “false male,” insinuating that Verbermacher pretended to be a male - in both appearance and action - probably in order to gain leadership in her sexist and deeply gendered community. Others, including Nathaniel Deutsch, suggest a more complex, non-binary gender identity that ultimately began to manifest itself after the trama of Verbermacher’s mother’s death and the subsequent bedridden illness. While Verbermacher herself never explicitly said anything about her gender identity this episode raises important questions about the way that historians, biographers, and even social commentators ascribe ulterior motives to complex scenarios surrounding identity, even at the risk of seriously offending the person involved.

Adorning tallit and tefillin daily, Verbermacher began studying Torah throughout the entire day, mimicking exactly what one would expect from a budding Hasidic rebbe. Slowly, Verbermacher’s fame began to grow and stories of her miracles and healing powers (not uncommon for Hassidic masters) started to spread. Verbermacher began teaching public Torah classes hidden behind a sheet (as it was forbidden for men to gaze at a woman in their community) - along with performing many of the other rituals set aside uniquely for rebbes such as receiving prayer notes, leading the Friday night tish, and even passing out shirayim (food leftovers for her followers to eat). All of this, of course, with Verbermacher hidden out of sight. It has even been suggested that Verbermacher would consciously attempt to sound like a man, speaking with a deep voice during these frequent leadership occasions.

But, perhaps unsurprisingly, this worried many in the community including Verbermacher’s own father, Monesh, who wanted to see his daughter marry and live a traditional female life. He ultimately brought his daughter to consult the Chernobyl Rebbe, the Hasidic leader at the time, and Verbermacher eventually acquiesced entering into a short lived marriage that would soon dissolve after Monesh’s death.

Other critics considered Verbermacher’s leadership to be a complete abomination within the strictly gendered and rigid Hasidic community. Not only, they argued, was Verbermacher, at this point known as a Maiden of Ludmir - an honorary type of title given to Hasidic leaders - not biologically related to any other Hasidic masters (an important point in the dynastic Hasidic world) but she was a female! Many such opponents pegged the Maiden as being controlled by an evil spirit (dybbuk) that was causing Verbermacher to act like a male and lead the congregation astray.

The idea that a powerful female in a patriarchal society was thought to have been possessed by an evil spirit may sound ludicrous but it was all too common throughout history. Similar to the accusation of witchcraft given to any outspoken women in many western societies, the claim that a person, especially a female, acting out of line was possessed by an evil spirit is ubiquitous in the Hasidic world - where elaborate rituals are composed to rid the body of the dybbuk.

Verbermacher, however, refused to be slowed by the detractors and spent half a century as a Hasidic rebbe gaining a following both in Europe and eventually Palestine after immigrating later in life. At the ripe old age of 83 the Maiden of Ludmir was buried in Jerusalem on the Mount of Olives.

Never in the history of the Hasidic movement was there another female rebbe.

What lessons can we derive from this story? Maybe it is just another case study, amongst hundreds of thousands, attesting to the complex nature of identity - be it gender, cultural, religious, etc. Perhaps it is a perfect example of the rule that “there is always an exception to every rule,” and that even in one of the most sexist societies in the world, a female was able to attain the highest level of leadership. Or maybe, highlighting a female leader in history simply serves as a small way to combat what the feminist historian Joan Scott bemoaned as the “problem of invisiblity” when it comes to learning about woman throughout history.

Whatever the lessons are, the Maiden of Ludmir can serve as an inspiration to all of us today.

Moshe Daniel Levine is a regular contributor of blog postings on Jewish Values Online. His blog, So You Have a Jewish Father, was selected as one of the three best for the third quarter of 5779. You can find it on the Jewish Values Online website at the tope left.

Please note: All opinions expressed in Blog Postings and comments on the Jewish Values Online site and through Jewish Values Online are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views, thoughts, beliefs, or position of Jewish Values Online, or those associated with it.

Discussion about the status of women in Israel has been featured heavily over the years. What is the biblical and rabbinic view of the status of women in Jewish society? What do the various movements in Judaism say about this?

Discussion about the status of women in Israel has been featured heavily over the years. What is the biblical and rabbinic view of the status of women in Jewish society? What do the various movements in Judaism say about this?See answers from Orthodox, Conservative and Reform rabbis here.

If you have a question about Jewish values that you would like to ask rabbis from multiple denominations, click here to enter your question. We will ask rabbis on our panel for answers and post them. You can also search our repository of over 800 questions and answers about Jewish values.

For more great Jewish content, please subscribe in the right-hand column. Once you confirm your subscription, you'll get an email whenever new content is published to the Jewish Values Online blog.

For more great Jewish content, please subscribe in the right-hand column. Once you confirm your subscription, you'll get an email whenever new content is published to the Jewish Values Online blog.

|

|

|

Jewish Values Online

Home | Search For Answers | About | Origins | Blog Archive Copyright 2020 all rights reserved. Jewish Values Online N O T I C E

THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN ANSWERS PROVIDED HEREIN ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL JVO PANEL MEMBERS, AND DO NOT

NECESSARILY REFLECT OR REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE ORTHODOX, CONSERVATIVE OR REFORM MOVEMENTS, RESPECTIVELY. |